Reflection Routines: The Role of Student Voice in Learning

Students need reflection routines and time to pursue them.

In our recent pop-up course, Rethinking School, an exchange between two of the more than 200 educators in the course resonated deeply with me. While considering the role of feedback and its indispensable complement — student reflection — Rob Policelli, a history teacher at Durham Academy, articulated a frustration many teachers share: “the perception of negative feedback as an indication of not being a ‘good fit’ in a way that prevents…learning from our failures and from our weaknesses.”

In response, Brigitte Leschhorn, an English teacher at MICDS in St Louis, described her commitment this year to explicit instruction and opportunities for students to “self assess and create their own narratives.” These “intentional moments to digest feedback” have shifted how students talk about their reading and writing. As part of this effort, she’s simplified her feedback and asked students to expand on it themselves. She noted, however, that she’s wrestling with two questions:

- When is the best time for self-reflection?

- How do I manage the content I’m required to cover with this important piece?

Many of us share Leschhorn’s questions and her battle with balancing content coverage and trying to disrupt the typical way learning experiences end, where summative assessments are handed back then tucked away or tossed with little, if any, time for reflection.

A Common Language: Competency-Based Learning and Reflection

My colleague Jason Cummings tackled time and reflection in a blog post, 3 Ways Online Reflection Promotes Learner Agency in an Age of Urgency. Now I’m eager to couple his ideas with the language that competency-based learning (CBL) provides, language that can inspire and make possible a culture of reflection.

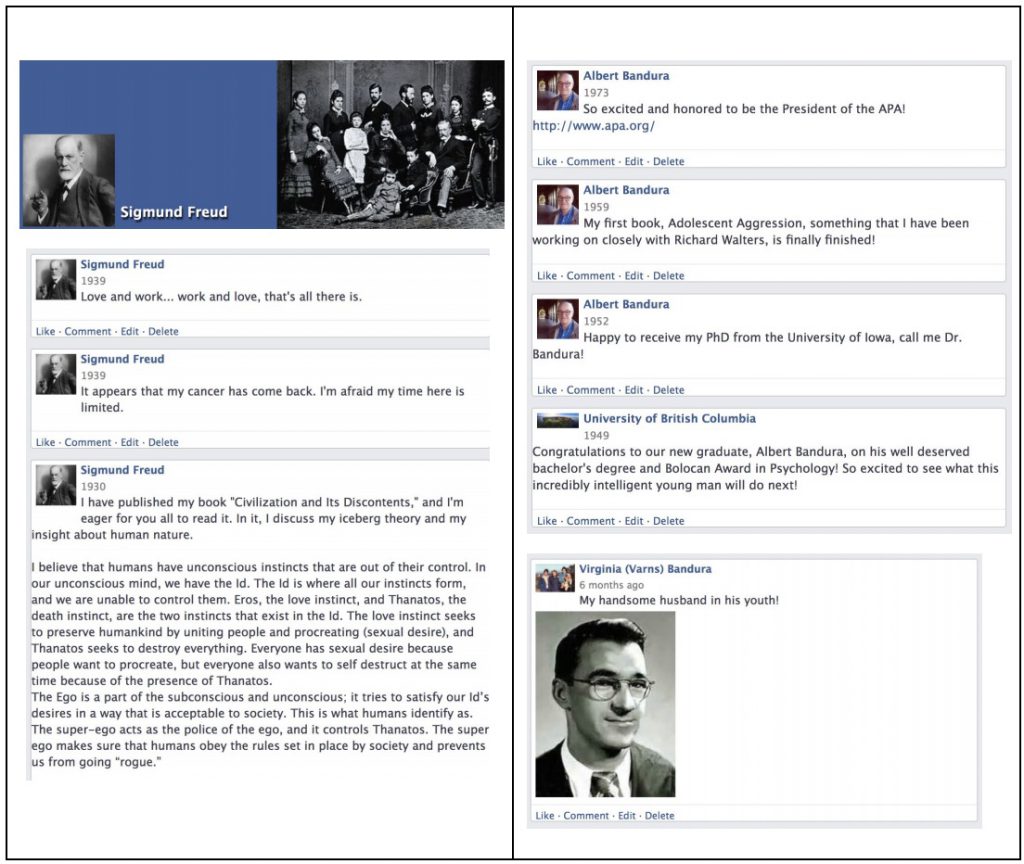

This type of reflection took place during a unit in GOA’s Introduction to Psychology on the history of psychology, where students pursued a modern take on psychology’s past and pioneers by researching, then becoming and developing a Fakebook page for themselves, posing as such figures as Sigmund Freud, Elizabeth Kübler Ross, and Albert Bandura. The unit began with the broad landscape of the field’s development, but the texture and depth of the history emerged with students’ research applied to becoming their chosen people and presenting a narrative biography, all the while using a fitting tone and style for their social media presence.

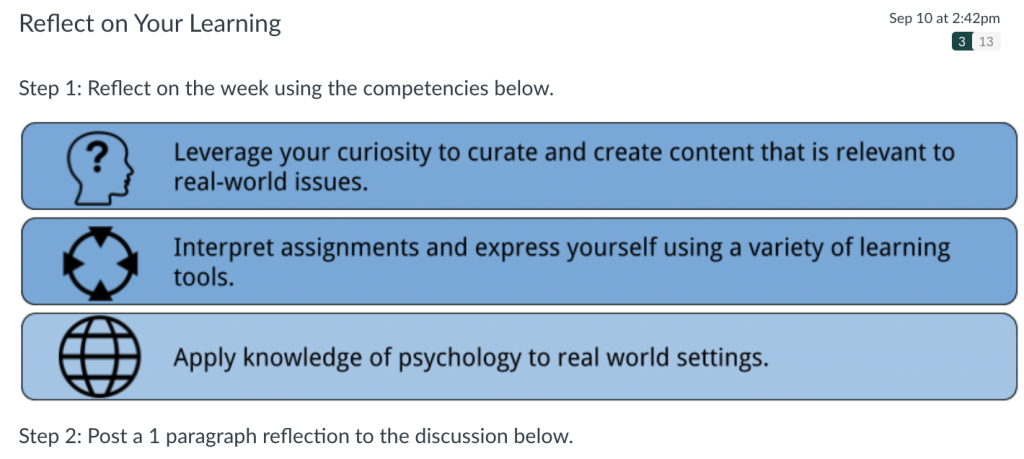

The unit concluded with competency-based reflections:

Here the student who became Sigmund Freud uses the target competencies in her reflections:

I’ve been able to make connections with [Freud’s Iceberg Theory] on a larger scale in the context of societies’ power structures, and I have been able to see why he came to the conclusion about the unconscious mind. When I think about different societies in the past that have come into power and then fallen, I realize that Freud’s ideas are very relevant. I will continue to see how Freud’s theory applies to other events in the world, especially in our governmental systems.

In a time where social media is one of the main ways to communicate with people, I thought that it was more interesting learning about the psychologists through social media pages and fun videos.

During this unit, I needed to be resourceful about finding sources for my Fakebook profile and video. The databases I used to look up information are definitely ones that I will use in the future. I liked how this unit was interactive and how we got to learn through our other classmates. It made me feel more connected to the members of the class.

Students now identify for themselves how well they developed the competencies and fulfilled the outcomes.

John Zebell of Christ Church Episcopal School, one of our psychology teachers, described how new reflection practices have led students to see themselves as a “work in progress,” rather than “a product we’re trying to maintain in perfect condition.” He added, “the language of our competencies doesn’t feel foreign or threatening to students, so they engage with it easily…and asking students to post their reflections in a discussion forum…creates…a community of support rather than competition. Seeing others admit that they have work to do breaks down walls and builds connections.”

Practice is Key

Learning the language of reflection is akin to learning any language. In our Arabic course, practicing reflection is as common as practicing vocabulary, grammar, and conversation. Listen to how this student, in composing a short video reflection, is developing fluency with her Arabic skills and her learning skills. She is, with increasing skill, weaving together ideas and questions about Arabic with metacognitive work.

Here’s to being curious. Here’s to what reflection can inspire when supported by competencies and outcomes, the language of learning. Here’s to giving students the time to “self assess and shape their own stories” and to step back from the doing and the deadlines and simply reflect and make meaning for themselves. Here’s to shifting how all students talk about their learning.

Global Online Academy (GOA) reimagines learning to empower students and teachers to thrive in a globally networked society. Professional learning opportunities are open to any educator. To sign up or to learn more, see our Professional Learning Opportunities for Educators or email hello@GlobalOnlineAcademy.org with the subject title “Professional Learning.” Follow us on Twitter @GOALearning. To stay up to date on GOA learning opportunities, sign up for our newsletter here.