Back to Basics, Not Back to “Normal”

Schools aren’t waiting for “normal” anymore.

In June and July, I led professional learning workshops at six different schools and, with Kawai Lai, facilitated two online leadership institutes and one in-person leadership retreat, connecting with more than 100 school leaders. I met schools and people who are eager to restore stability to their communities so that they can do their work with a sense of security and an eye towards the future.

Importantly, these schools rejected the notion that “stability” means simply reincarnating the ways they looked and operated in 2019. They are focusing on closing what Melissa Daimler calls “culture gaps,” places where systems, behaviors, and practices must be improved or redesigned to align more authentically with core values. Instead of “back to normal,” schools are going “back to basics,” reinvesting in and updating core elements of identities and programs to reflect what they have learned from the disruptions of the past two+ years.

Revisiting Five Basics of School

Culture: Schools should be places of belonging and empowerment for both students and adults.

Student panels, like this one at Phillips Academy Andover (MA), are becoming a core part of professional learning experiences.

In every learning experience I was involved in, there was open acknowledgment that the way schools operated in 2019 did not offer balance or stability to all community members. Instead, schools are recalibrating school culture, especially when it comes to ensuring a sense of belonging for students and staff from marginalized groups. I was struck by how schools were building professional learning around listening to voices from inside the community: hosting student panels, forgoing lectures by outside experts to make time for teacher-led design, and creating significant space on agendas for open reflection and discussion of how team dynamics and practices need to shift to support increased belonging. This epitomized the “back to basics” approach for me: a recognition that the most basic element of school health, its culture, needs work.

Learning: Durable, transferable competencies offer shared goals and vocabulary.

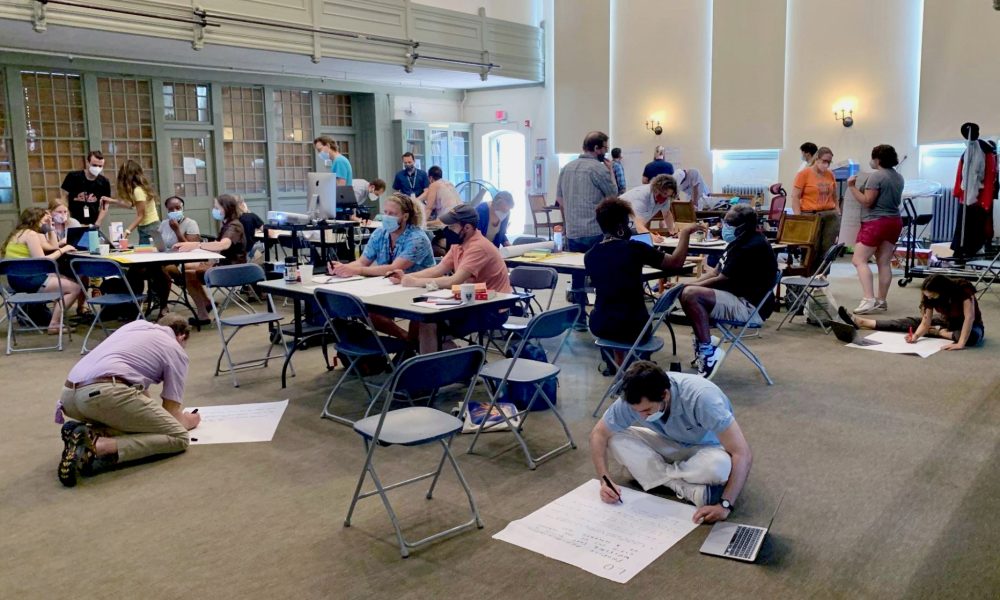

A rubric design sprint at Germantown Friends School (PA) asked teachers to articulate learning outcomes of their courses as durable, transferable skills.

The schools I worked with recognized that one part of pursuing belonging was aligning on shared, learner-centered goals. One way to introduce more flexible, equitable approaches is to articulate learning goals as competencies (durable, transferable skills). I led several design sprints with schools seeking to realign around critical skills within and across academic disciplines. Whether they were working on a Portrait of a Graduate or prototyping competency-based rubrics, these sprints revealed that teachers across departments aligned on skills students need to find meaning and navigate challenge: give and receive feedback, connect learning to personal and community goals, reflect openly and in community, advocate for yourself. The impact of the ongoing disruption to these educators’ lives and the lives of their students has created a sense of urgency to rearticulate and recommit to lifelong learning skills.

Partnerships: Deepen ties to the local community.

Educators at Phillips Academy Andover visited Chùa Tường Vân Lowell, one of several Buddhist temples within a few miles of the school.

Now more than ever, students and teachers want to know the work they do in school has meaning and value in the world beyond it. Three of the schools I worked with explicitly connected their work on competency-based goals with visits and connections to local organizations. One of the benefits of competency-based, rather than content-based, goals is they open new possibilities about where and with whom learning can happen. Whether they were exploring partnerships that had already sparked meaningful student-led learning (Andover’s “Listening to the Buddhists in Our Backyard”) or establishing new relationships with sustainability-focused organizations (Parker School) or refreshing their commitment to community engagement in the wake of pandemic education (The Delta School), these schools want to move beyond the traditional field trip by embedding community partnerships and experiential learning in the core curriculum. By incorporating visits and networking with local partners into professional learning experiences, schools are investing in teachers’ ability to align the design and content of the curriculum to issues facing their communities.

Teaching: Prioritize joy, purpose, and sustainability.

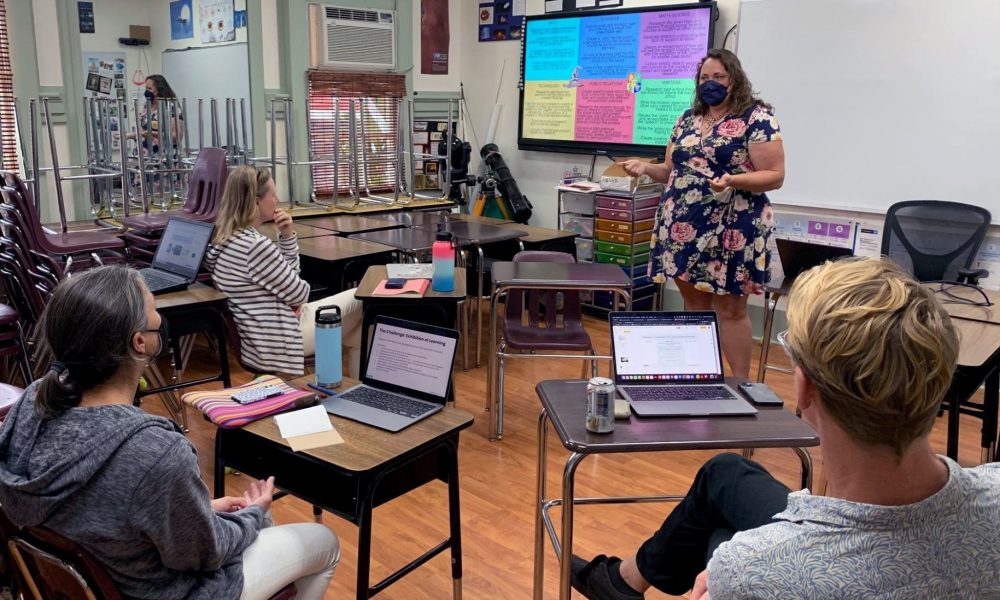

Teachers at Parker School designed prototypes for new learning experiences and pitched them for feedback and iteration.

The disturbing state of the teaching profession has been well documented, leading to important conversations about wellness, compensation, and how we define a teacher’s job. When it comes to professional learning, in my experience, these challenges have not manifested as teachers refusing to work, learn, or grow. In fact, I’ve experienced the opposite: teachers are deeply interested in working on their craft after more than two years of feeling disconnected from it. However, they want an authentic voice in what professional learning looks like and how it affects the evolution of their schools. The most successful teacher professional learning experiences I led in June and July had a few key ingredients: 1) school leaders were in the room, participating actively and answering questions about institutional efforts that would support teacher efforts, 2) teachers were able to work in small groups and propose their own solutions to real challenges, and 3) they were able to articulate how shifts in practice would enhance sustainability, especially around workload. In other words, schools prioritized learner empowerment and relevance in professional learning, much as they want their teachers to do for their students.

Leadership: Practice, not policy. Modeling, not management.

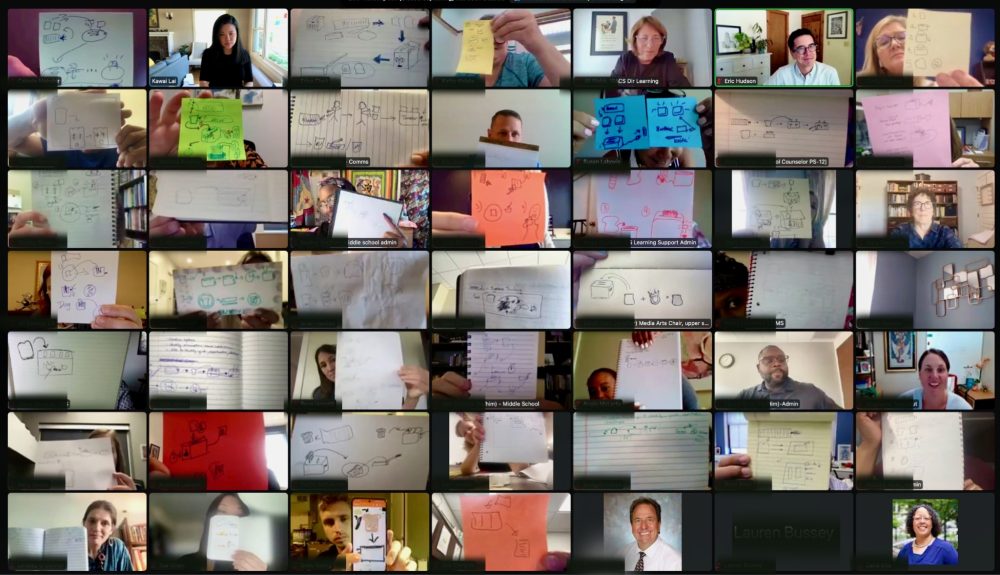

Leaders are interested in building concrete, relevant skills like systems mapping (seen here at the ISACS New Leaders Academy) that help them navigate the increasingly complex nature of their jobs and the schools they serve.

The current climate in schools calls for human-centered leadership. For school leaders I’ve met, many of whom are new to their roles and/or their schools, they want to learn concrete and practical ways to embed empathy and care into their daily work while still fulfilling their core responsibilities. These skills include communicating with clarity, facilitating meetings that are meaningful and equitable, making decisions in the face of ambiguity and uncertainty, and having challenging conversations. These leaders’ determination to listen to their communities, to act on what they hear, and to model learner-centered behavior reminded me of Ted and Nancy Sizer’s The Students Are Watching. School leaders are less interested in changing their schools for the sake of innovation or ambition and are more interested in strengthening their schools by ensuring they authentically reflect and act out core values both implicitly and explicitly.

What inspired me most about this recent work I did with schools, educators, and leaders was a refusal to wait for stability to organically return. Waiting for “normal” isn’t the right strategy. If schools have learned anything, they have learned that uncertainty and instability will continue, and that requires them to be proactive in nurturing the basics: culture, programs, and people.

The partnerships and workshops described in this post are a part of GOA’s consulting services. We work with educators and school leaders on initiatives that support meaningful learning experiences for students and adults. To learn more, explore our services and submit an inquiry.

For more, see:

- Back-to-School Professional Learning: What Educators Need in 2022/2023

- The Power of Collective Purpose in Schools

Rethinking Professional Development at Your School Post Pandemic

GOA serves students, teachers, and leaders and is comprised of member schools from around the world, including independent, international, charter, and public schools. Learn more about Becoming a Member. Our professional learning opportunities are open to any educator or school team. Follow us on LinkedIn and Twitter. To stay up to date on GOA learning opportunities, sign up for our newsletter.