How to Design for Learning: Four Approaches to Nonlinear Curriculum

Is school designed for the way humans learn?

In many ways, the traditional, time-based system of school isn’t compatible with learning, especially the linear design of what we’ve come to understand as a “course.” As Dan Cristiani of The Nueva School argues in this post, we organize academic programs into courses for practical reasons, like scheduling and grading and teacher load, yet our efforts to be efficient and organized can run counter to our missions to give every student the chance to learn deeply.

Based on research in cognitive science, we know the learning process is nonlinear: different students need different amounts of time, support, and modalities in order to learn. Along the same lines, the idea that there is a “correct” sequence to curriculum is under increasing scrutiny. While historically we have planned courses as single straight lines, we need to start thinking in terms of spirals, webs, latticework, and other, more complex shapes.

What does nonlinear curriculum look like? Lately, I’ve been inspired by educators who are putting new models into action right now, thinking about innovative designs that support the ways we actually learn.

1. Parallel Units

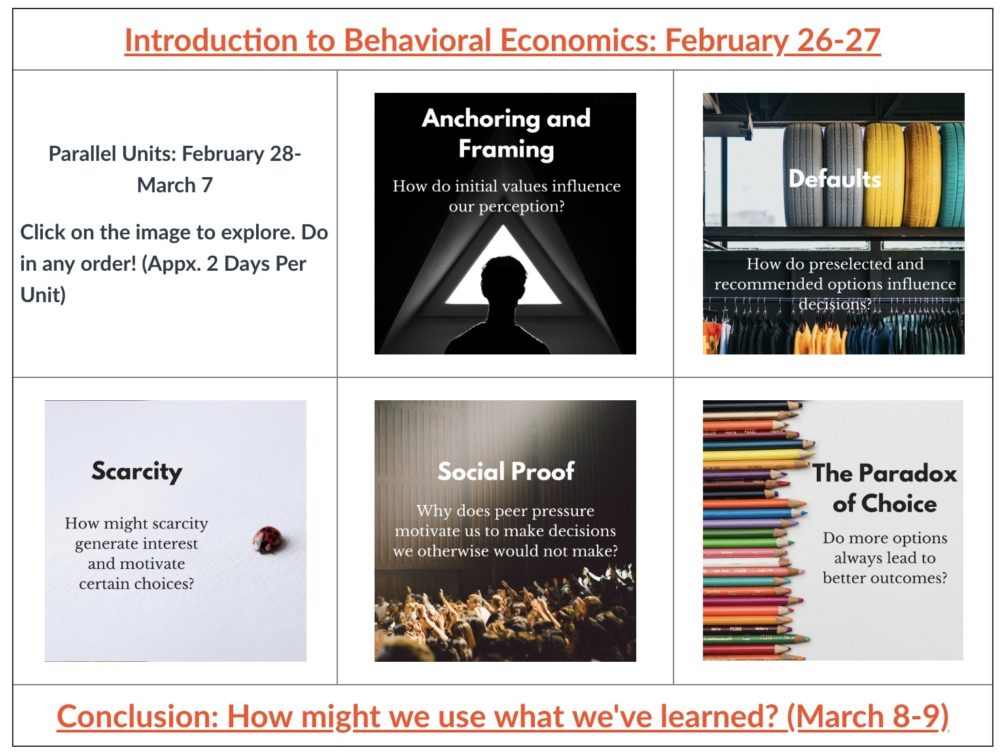

In GOA’s flex course, “Designing Decisions,” the teacher, Adam Lavallee of Episcopal Academy, decided to introduce five mini-units in parallel rather than in sequence. After a two-day, whole-class introduction to the field of behavioral economics, students could choose both which topics they wanted to explore and in what order they explored them. Each unit was structured in a similar way: key content, opportunities for discussion, and an experiential activity for students to find the topic at work in their own communities. Publishing these units in parallel allowed students to move freely, navigating among units to develop a broader understanding of the field and/or spend more time with individual units for deeper learning. At the end of the course, the students flowed back together to reflect on their various experiences and find shared understandings.

Question for Teachers: What would it look like to reframe a course so that, instead of a series of units in sequence, you presented those units in parallel, allowing students to make choices about when and how they learned key concepts?

2. Skill Trees

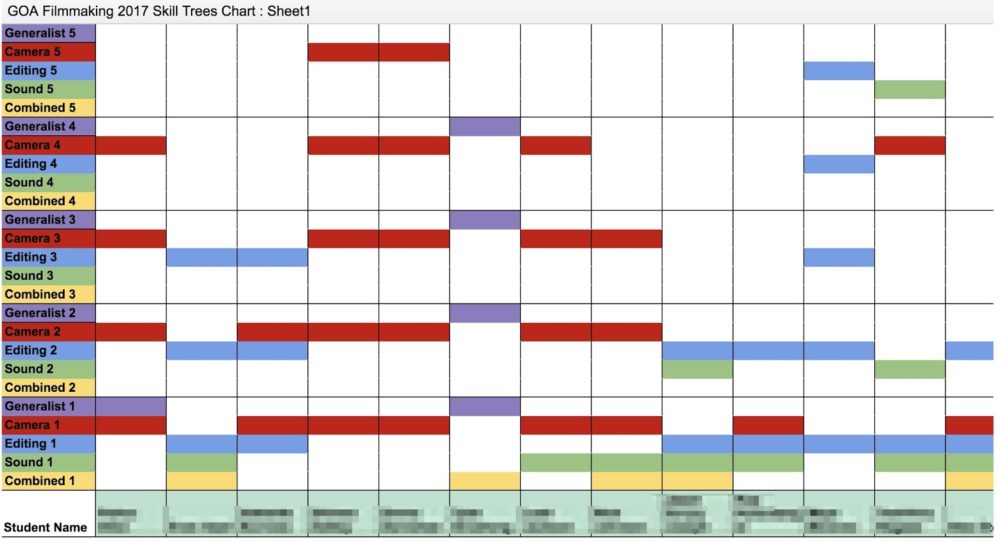

In GOA’s Filmmaking course, teacher Brendan Gill of Catlin Gabel School has taken inspiration from video game design to build his course around skill trees. He’s broken the topic of making films into five skills — Generalist, Camera, Editing, Sound, and Combined — and created five “levels” for each skill. Each level has its own content and project for students to practice and demonstrate competency. Students document their progress via a shared Google Spreadsheet (above), and, based on the height and color combination on the spreadsheet, Brendan and his students can see how they are mixing and matching skills. All students come together for “Crit Days,” where, once a week, students share their individual projects — no matter which tree they’re on — for peer feedback and conversation.

Questions for Teachers: How would you break down units or core concepts in your course into discrete skill trees, each with its own set of levels? How would you help students make decisions about becoming “generalists” or “specialists” in your class?

3. The Birdhouse Model

Educators Douglas and Mary Kiang have designed an Introduction to Computer Science course using MakeCode for micro:bit. While their focus is on introducing computational thinking concepts using a particular tool, their curricular framework, inspired by Kris Schwengel’s Makerfesto, has universal applications. Each lesson begins with an “Unplugged Activity,” a device-free, interactive activity that illustrates a computer science concept (algorithms, say) using movement or making. What follows is the “Birdhouse Activity,” named after the classic beginner woodworking project. In this stage, all students do the same activity as a way to practice and solidify skills with their devices. Critically, after this relatively linear progression, every lesson opens out into a creative project. Students use a simple prompt to design something of their own, weaving in previously learned skills but ending up with different products. Learning in the Kiangs’ course isn’t complete until students have a chance to think creatively, a hallmark of higher-order thinking.

Questions for Teachers: How many of your lessons culminate in a birdhouse activity instead of a creative project? How might you redesign or extend a lesson to open it up to student voice, choice, and agency?

4. Greenlight Spreadsheet

Almost buried in this terrific post on grading from educator Matthew Cheney is a simple framework for making assessments less time-based and more performance-based. “We use a ‘greenlight’ system,” he writes, “where the students can revise their work until it reaches an acceptable level (gets a green highlight on our course spreadsheet), and they pass the course if all of their assignments are greenlit.” Not only does this spreadsheet remove the deadline as the driving force of curriculum design, it recognizes reflection, revision, and spaced practice as core elements of learning, where students are given as much time and support as possible to produce their best work.

Questions for Teachers: In his book An Ethic of Excellence, Ron Berger argues student work should be either “an ‘A’ or ‘Not Done.’” Do you agree with this statement? How might you use a simple greenlight spreadsheet to allow students more time and space to revisit and revise their work until it reaches its highest quality?

It would be a mistake to equate nonlinear curriculum with poorly planned or “loose” curriculum. These four examples reflect the structure and guidance we know students need in order to learn best. However, we can be — and should be — more flexible, more open, and more playful when creating the systems and conditions that allow students to learn. I believe these models, and others like them, are leading what will eventually become a paradigm shift in education: the adoption of learning architectures that are as interesting and diverse as learners themselves.

GOA would love to see and learn from more examples of nonlinear learning design. Share them with us on Twitter or send us an email: hello@globalonlineacademy.org.