Flexibility, Wellness, Sustainability: GOA’s Review of School Schedules for Learning Online

This is the first post of a two-part series on scheduling and grading during COVID-19. You can read the second part, on grading policies, here. For all of GOA’s resources and offerings related to learning online at this challenging time, please visit our COVID-19 landing page.

In early April 2020, GOA conducted a survey of independent and international schools, hoping to gather data about how they were approaching schedule and grading policy while learning online during the COVID-19 crisis. The goal was to gather and share information in an organized way during a time of rapid, challenging change. In our many conversations with educators and school leaders, schedule and grading were two topics where they were eager to learn from each other.

The Survey by the Numbers

GOA analyzed the responses of 89 independent and international schools, 34 of which are members of our consortium. Of the 89 respondents, 63 are based in the United States. Sixty-three schools have an elementary school division, 73 have a middle school, and 77 have a high school. Twelve of the respondents serve only elementary and/or middle school students. (List of respondents). Dates of an official move online ranged from January 27 to April 6, 2020, with the majority of respondents moving online sometime in March.

The survey asked a series of questions about how schools designed schedules and grading policies for a move online. The survey included a request for samples of and rationales for schedules and grading policies. This post focuses on scheduling.

What the Data Showed

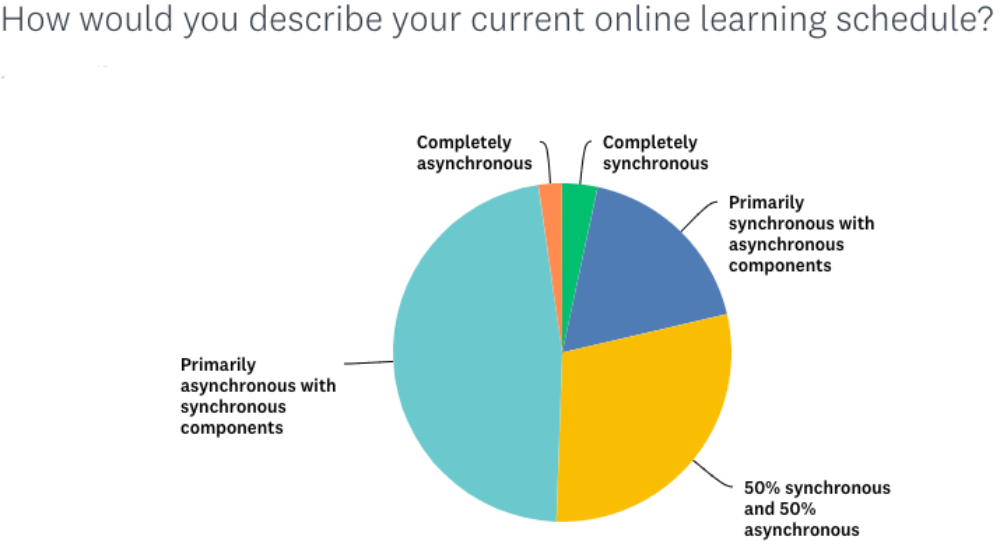

The overall data shows that the vast majority of schools are mixing synchronous (happening in real time) and asynchronous (happening at different times) learning. Of the 89 respondents, 26 schools (29%) describe their schedules as evenly split between synchronous and asynchronous learning. Forty-two schools (47%) describe their schedules as primarily asynchronous. Only 21% of respondents described their schedules as primarily or solely synchronous. When asked about the rationale for their schedules, schools shared responses that fell into three major categories:

- Flexibility: Learning and working remotely looks different from student to student, family to family, and educator to educator. Flexibility in schedule is important.

- Wellness: Worry about screen time, stress, and pace while learning remotely drove many schools to consider carefully how much and how often students were expected to be on video calls.

- Sustainability: Maintaining a rigid schedule of primarily synchronous learning is overly demanding for most students and teachers, and it was impossible for most international and boarding school respondents, where students, educators, and their families are spread across as many as 12 different time zones.

Key Trends

How these major considerations manifested in the actual design of schedules varied from school to school, but in most cases schools could not simply replicate their daily schedules online. For reasons of flexibility, wellness, and sustainability, they had to make some concrete changes. When we look at these changes across a large group of schools, a few trends emerge.

- Culture and Relationships Drive Synchronous vs. Asynchronous Decisions. The majority of sample schedules included designated synchronous time for a co-curricular, extra-curricular, or community purpose. For students in grades 3-5, Graded School reserves synchronous time for class meetings and one-to-one calls with the teacher. Lakefield College’s schedule begins each day with synchronous, community-focused meetings. Pomfret School (schedule) and Culver Academies (schedule), which have primarily asynchronous schedules, use synchronous time for advising, conferences, and tutorials, not direct instruction. Charles Wright Academy students have two synchronous class meetings per week, with community meetings, family meetings, and teacher conferencing filling out remaining synchronous time.

- Longer Blocks. Many schools who might have had six to eight blocks in a day moved to fewer, longer blocks each day. Kingsway College students begin mornings and afternoons with synchronous lessons, then have a total of three hours of asynchronous time to focus on movement, passion projects, or class work. Menlo School has created a simple five-day, primarily asynchronous schedule that has ten three-hour blocks. As you can see on this schedule, certain blocks may meet synchronously once a week (how much of that time is actually synchronous is up to the teacher), with students responsible for planning the rest of their time.

- Later Starts or Earlier Ends for “Instructional Time.” In thinking in new ways about time, many schools are beginning synchronous class time or “taking attendance” later in the day, perhaps a nod to the growing body of research that students would benefit from a later start. You can see evidence of this in the Pomfret and Culver schedules shared above as well as Catlin Gabel School’s schedule. Schools still starting at more traditional times like Loomis Chaffee (schedule), Greens Farms Academy (schedule), and The Bush School (schedule) are offering asynchronous learning in the afternoon. As Windward School’s schedule notes, this might result in less “instructional time” as defined by synchronous time with a teacher.

- Overall, the Younger the Student, the More Asynchronous the Learning. Among the respondents, most elementary schools have primarily asynchronous schedules, relying on support from families at home to implement learning plans designed by teachers. Graded School’s Distance Learning Plan offers a comprehensive overview of how one school shifts its schedule as it moves from pre-kindergarten through high school.

- Seeking Balance. Many schools have made, and are making, adjustments to their schedules—especially those schools who have been online for longer—usually to strike a better balance between synchronous and asynchronous learning. Elementary schools that began as fully asynchronous have begun to integrate synchronous elements. High schools that began by replicating daily schedules that were primarily synchronous have backed off. Billings Middle School’s schedule reflects clear decisions to balance synchronous and asynchronous time. The Watershed School has alternated synchronous time between mornings and afternoons.

The Impact on Teaching and Learning

Some schools noted the impact of a redesigned schedule on teacher practice.

“Moving from a seven-day to a [five-day] schedule simplified planning and got teachers thinking in five-hour chunks of time that they could design in pursuit of one or two-week modules. It also made work and school more predictable with parents' work lives and made for more consistent contact between teachers and students,” said Derek Kanarek, Upper School Academic Dean at Catlin Gabel School

Lauren Bowers, Instructional Coach at the American School of Dubai, identified the need for professional learning in order to ensure schedule shifts are effective: “By collaborating with schools who have been in this for a while, there was overwhelming advocacy for asynchronous learning. This is a time for students to really explore a personalized learning approach that is self-paced (within reason). However, I think in order for this to best serve our students, there also needs to be a shift in the approach of delivering instruction, designing assessments, and providing proper scaffolding, pacing, and graphic organizers to support this work.”

Responsive Design

Learning from these 89 schools reminded me of this terrific post by Mike Crowley, where he quotes the Executive Director of the World Health Organization, Michael Ryan:

“If you need to be right before you move, you will never win. Perfection is the enemy of good… Speed trumps perfection. And the problem we have in society at the moment is everyone is afraid of making a mistake... The greatest error is to be paralysed by the fear of failure.”

It’s worth repeating that respondents who have been learning online for weeks or months continue to make adjustments to their schedules. Many schools reported collecting regular feedback from students, teachers, and families, feedback that drives shifts in schedule and other policies. None of the schools claimed utter confidence in their models; in fact, most respondents were eager to see these results so they could continue to learn from each other.

In that sense, these schools, many of which are large and well-established, have become start-ups: tackling a novel problem, paying close attention to those they serve, acting quickly, iterating constantly, and not adopting a system solely because it’s the one they have right now.

Recommended Resources

- Culver Academies | Expectations and Guidelines for Online Learning

- Graded School Distance Learning Plan

- Lakefield College’s Weekly Routine

- Pomfret School Distance Learning Hub

- Remote Learning at Charles Wright Academy

This is the first post of a two-part series on GOA’s Schedule/Grading Policy Survey. You can read the second part, on grading policy, here. Visit GOA’s COVID-19 landing page for our latest resources, offerings, and events. To learn more about our approach to online learning, explore our Student Program and Professional Learning offerings.