How I Used Data Visualization to Design Better Discussions

On occasion, GOA will invite guest contributors to the blog. Here, Paulette Unger, Upper School Science Teacher at Christ Church Episcopal School (CCES), shares how teaching online with GOA helped her design better discussions, online and on campus.

The best online discussions don’t look that different from the best in-person discussions.

When it comes to any discussion, we want students to listen and respond, to dig deeply into their ideas and those of others, and to interact more readily. Through an ongoing, collective exchange of ideas, students are more apt to gain empathy and understanding of multiple viewpoints on current issues and new ways to approach and solve problems.

Meeting these goals in an online discussion, however, requires students and teachers to build a few new habits, most importantly being intentional and proactive about how we’re keeping the interactions lively.

It wasn’t too far into my first semester of teaching GOA Bioethics that I found myself pondering, “Why are my students not revisiting discussions?” Even with specific instructions to do so or my promise to attach a grade to their replies, students seemed to struggle to keep the conversation moving. Many posted their initial thoughts, asked a question to a peer, and then were never heard from again.

One of GOA’s core student competencies is to collaborate with peers who are not sitting next to you, and online discussions are a valuable opportunity to build this skill. How might I, as the teacher, design elements for online discussions that would entice students to stay connected to the conversation beyond their initial visit?

Make the Conversation Visible

With Threadz, a visualization tool for Canvas, discussions are illuminated in a whole new way. In Bioethics, each module began with a Plunge-In discussion for students to share their initial views on a topic and its ethical issues. Threadz analyzed interactions in the discussion and produced a “chord image,” which allowed me to quickly see which students posted a thought, comment, or asked a classmate a question.

It also brought to light that, beyond any initial posting, there didn’t seem to be much mixing of colors, meaning the critical exchange of ideas wasn’t happening.

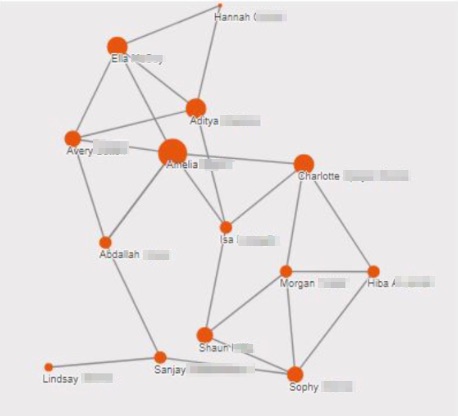

By shifting next to a Threadz “network view,” I could look more closely at a student’s contribution by the size of each orange sphere. I was able to note learners who were leading the conversation, those students who were missing, and those who were isolated from the conversation.

I shared this image with my students on Slack, and proposed a “Threadz Challenge” to see if they could enlarge their very own orange bubble, their spheres of influence and interaction, by revisiting the conversation. I made the analogy to a workout challenge, but instead of building muscle, students were building skills that would lead them to mastery of course outcomes. They had 48 hours and the clock was ticking.

The image was a powerful motivator. A follow-up Threadz image revealed full class participation and an overall increase in student posts and replies.

Additional Threadz statistics can be used to quantify these colorful images and find out the actual number of student posts and word counts. The visual data helps teachers get a quick glance at overall trends in a discussion, later enabling them to more fully focus feedback to each student.

Make Students the Experts

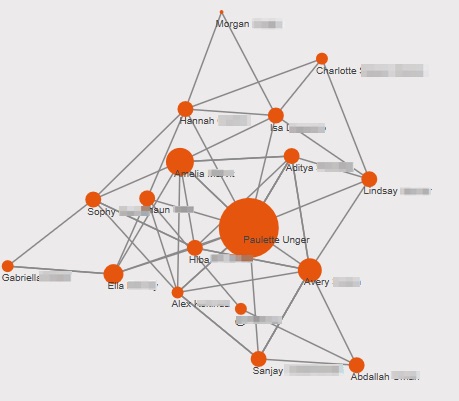

As educators, it’s our instinct to jump in when students pose questions and offer insights. Online discussions are no exception. However, it may develop into a more fruitful discussion if we step back and let the students take the lead. Too many posts from a teacher might intimidate students who are cautious when it comes to their online presence and how their ideas may be interpreted. A strong teacher presence can also send the message that it’s more important to be listening to what the teacher has to say and not to what other students have to say. This Threadz image shows a teacher-centric conversation a bloated circle looming on the screen.

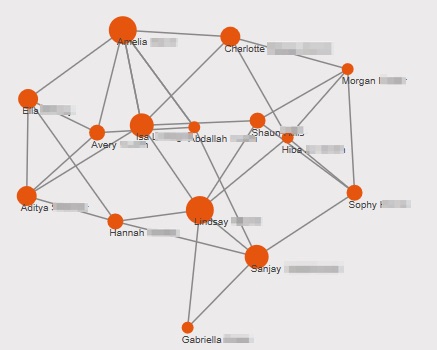

We can use design strategies and data to empower students to lead the conversation. During a Bioethics module in which students were researching various ethical cases involving human subjects, students had to generate top ten list of rules or guidelines that researchers need to follow. The discussion was designed to build student competency with collaboration skills. Students felt a more genuine purpose that required them to more frequently visit the discussion and dialogue. The Threadz image from that discussion highlights these mutual exchanges and allowed me to offer targeted, actionable feedback based on the data.

Bring Online Discussions to Your Classroom

Time is the resource teachers can never have enough of. While teaching for GOA, I found myself drawing from my online experience to try to find ways to utilize technology in my CCES classroom to acquire more time for learning. In the midst of winter, when snow days and illness made for staggered student attendance in my brick and mortar classroom, I had to get creative: my Honors Biology students used Google Slides and screencasting tools to prepare narrated lab presentations for sharing and discussion in CCES’s learning management system (LMS). I invited sick students to “come to class” via FaceTime. I used Zoom to hold snow day meetings with my thesis advisees.

Recently, my freshmen spent class time identifying a question of interest about environmental factors that might affect the rate of photosynthesis. They worked collaboratively in small groups to conduct background research and design and carry out their controlled experiment to try to find an answer to their question. When it came time to share their findings, they had to compile their data and claims into a narrated presentation and post to our online class discussion to learn from each other, gather feedback, and answer questions. I was in awe as I watched my students ask probing questions of each other. Even more rewarding was to see them answering the questions and thanking each other for the ideas. They were checking back into the discussion throughout the weekend without my having to nudge them along. Their reflections on the goals of the assignment were more profound and meaningful than they would have been had they not taken such ownership and engaged so deeply in this discussion.

As one student said to me, “It was cool to be the experts on something.” Whether the discussion was online or not mattered less to them than how much ownership they had over it.

Paulette has served almost 20 years as a classroom educator teaching various levels of Biology, including AP and IB Biology. She is a College Board exam reader and consultant and conducts training workshops for new and experienced educators. Whether it is discussing the ups and downs of college life with her step-daughter, Brianna (age 21), shooting hoops with her son, Lucas (age 8), or dancing the sillies out with her daughter, Elena (age 2), there is never a dull moment in her day. Follow Paulette @ungerpl

For more, see:

- All That Jazz: Using Feedback to Make Learning Visible

- From Theory to Practice: How Teachers are Implementing Competency-Based Learning

- How to Use Online Learning to Enhance On-Campus Conversations

Global Online Academy (GOA) reimagines learning to empower students and teachers to thrive in a globally networked society. Professional learning opportunities are open to any educator. To sign up or to learn more, see our Professional Learning Opportunities for Educators or email hello@GlobalOnlineAcademy.org with the subject title “Professional Learning.” Follow us on Twitter @GOALearning. To stay up to date on GOA learning opportunities, sign up for our newsletter here.