How to Design a Feedback Ecosystem

Learners thrive on feedback.

Good feedback provides us with the information, the motivation, and the structure to learn deeply. As Grant Wiggins argues in “Seven Keys to Effective Feedback,” if we spent less time teaching and more time giving feedback and supporting students in applying it, students would learn more.

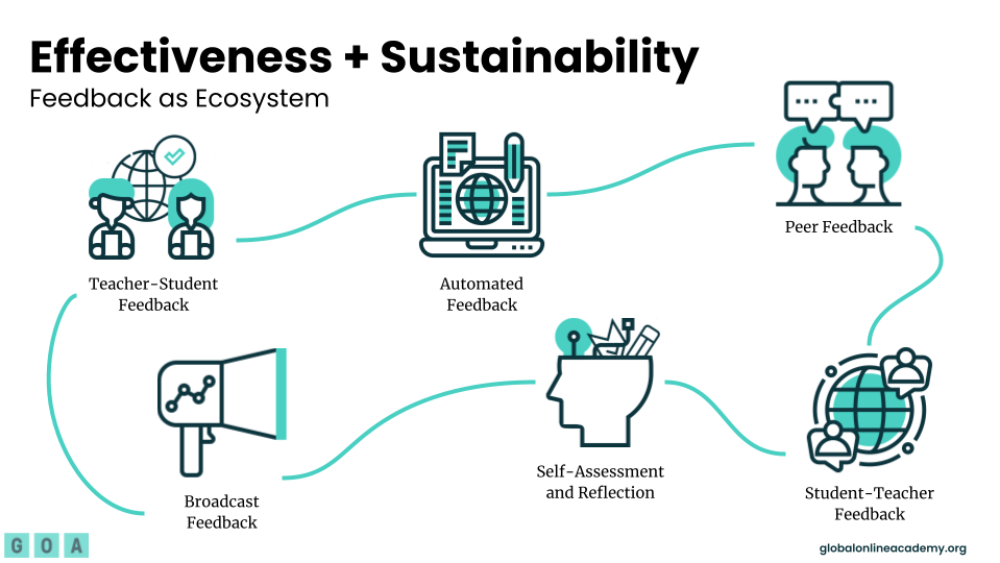

While we know that feedback matters, we also struggle with how to ensure that it is effective while still being sustainable. One way to navigate this tension is to think of feedback not as a single, one-way communication from teacher to student, but rather as an ecosystem made up of different strategies that work together.

Healthy ecosystems are balanced. In a feedback ecosystem, learning experiences include different forms of feedback, each used at a time and in a context where it can be effective for student learning. Decisions about when, where, and how to use these strategies should aim to empower students to drive their own learning, and each other's.

At GOA, where we work online with global cohorts of students, a strategic approach to feedback is essential not just for learning, but for establishing relationships with and engaging students. Feedback ecosystems can play a powerful role in building collaborative communities, one of GOA's core educator competencies.

Six Elements of a Feedback Ecosystem

1. Teacher-Student Feedback

Teacher-student feedback is often regarded as the "best" form of feedback, but its effectiveness depends on how well it is designed for students to use it. Because timely, specific, and personalized feedback from a teacher can consume a significant amount of our time and cognitive load, we should be strategic about its use, aiming to deliver it in formats and at times when students will benefit most from it.

When to Try It: Try feedback conferences to deliver high-quality, individualized feedback in the middle of a learning experience, not after it's over. Feedback that takes the form of conversation gives the student the opportunity to react to and reflect on your feedback, and it also gives you a chance to see and hear how students process it. These conferences can follow a simple format, and they don’t need to be longer than a couple of minutes. Online tools like VideoAsk or Mote allow you to start an asynchronous feedback conversation.

2. Automated Feedback

Automated feedback, or feedback delivered via technology when prompted by a learner action, is immediate, a critical element of effective feedback. When a student submits an answer on an online quiz or responds to a question in a video or on a webpage, they see and can act on the results without having to wait for someone else to tell them how they did. While feedback in this format isn’t as complex or nuanced as other types, it can provide students with helpful information when they need it.

When to Try It: Move some formative assessments like quizzes into your learning management system (LMS) or into an online tool like Quizlet. Ensure answers are pre-populated and informative. Embed interactive elements into instructional videos using tools like VideoAnt or Nearpod. In both cases, students should have the chance to correct their answers and make multiple attempts so they can master key concepts in less of a time-based way.

3. Broadcast Feedback

Broadcast feedback is designed for and delivered to a group. We often think of feedback as a private interaction between a teacher and a student, and in many scenarios, that’s appropriate. However, offering feedback to a whole group can spark meaningful conversation as well as avoid the repetition and redundancy that can come from giving the same individual feedback over and over.

When to Try It: Use broadcast feedback to examine student work together with your class. By gathering a group to examine an excellent model, you are providing useful information that students can apply to their own work. Do this live or use a screencasting tool like Loom to create instructional videos. Ron Berger has written extensively about the benefits of examining high-quality models with students.

4. Peer Feedback

As part of Berger’s focus on student work as a foundation for meaningful feedback and learning, his now-famous video “Austin’s Butterfly” captures two key ideas about peer feedback: it can be meaningful and students need time and space to learn how to do it kindly and well.

The Story of Austin’s Butterfly

EL Education

Spending time with students learning and practicing effective peer feedback has multiple benefits: it can build community, it can create a sense of student ownership over the work of the class, and it can support effective metacognition.

When to Try It: Use rubrics for meaningful teacher and peer feedback. By designing rubrics with clear, student-friendly language, they can become an anchor for peer feedback (see: “HyperRubric”). When rubrics are used as part of a peer feedback protocol, you can empower students with the knowledge and tools they need to improve each other’s work.

5. Self-Assessment and Reflection

As Lisa Son, Nicole Furlonge, and Pooja Agarwal write in this guide to metacognition, students need to routinely monitor their own thinking in order to develop deeper understanding of what they know, what they don’t know, and what actions they need to take. Making time for reflective prompts, for metacognitive activities like self-explanation, and for documenting thinking through writing or visualization helps students develop the ability to give themselves effective feedback.

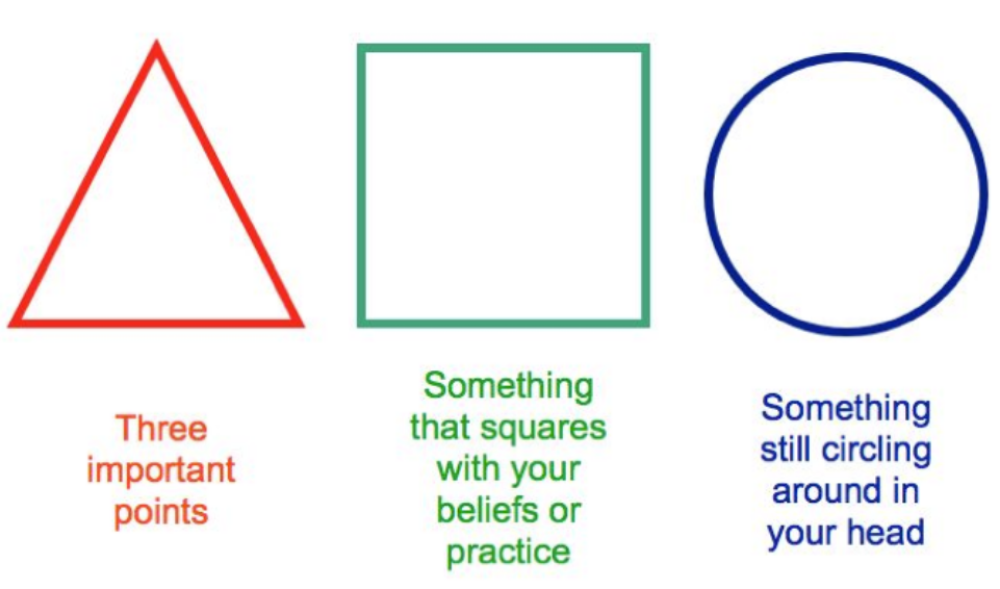

When to Try It: Integrate reflective pauses into lessons. Using simple prompts like the one below (here are dozens more), can create brief interludes in class for students to process learning. Mix and match silent writing with conversation with visualization with online tools to ensure students are exposed to a variety of ways to reflect on and document their thinking.

6. Student-Teacher Feedback

Student-teacher feedback isn’t just about students sharing what they think of us; it’s about asking students to share how they are, what they know, and what they need to know. Building regular ways for students to give us feedback not only makes us better teachers, but builds a culture of feedback and supports psychological safety.

When to Try It: Make entrance and exit tickets routine and feedback-oriented. A simple exit ticket prompt like “What was most helpful about today’s class? Least helpful?” can produce useful feedback. Check-ins like a “Rose and Thorn” protocol gives students the chance to share what they are thinking and feeling.

In a Healthy Ecosystem, Students Act on Feedback

As researcher Dylan Wiliam has shown, what feedback looks like is less important than what students are able to do with that feedback. The way you mix and match these six forms of feedback will vary from school to school, class to class, and learning experience to learning experience; however, students will always need the time, space, and support to demonstrate that they understand feedback and can use it to improve their work. When students become adept at receiving, giving, and using feedback, you’ll know your ecosystem is thriving.

To learn more about high-quality feedback in any learning environment, read these GOA articles:

GOA reimagines learning to empower students and educators to thrive in a globally networked society. To learn with us, visit our professional learning course catalog, explore our consulting and design services, or inquire about becoming a member school.