Four Strategies to Make Grading Effective, Equitable, and Sustainable

We have to talk about grading.

Educators often sidestep conversations about grading because the topic is deeply personal. As Joe Feldman notes, grading is closely tied to our identity as teachers: it stems from how we ourselves were graded and it often serves as a signifier of the rigor of our courses and the quality of our teaching.

Yet, grading has an outsized impact on how our students experience school and on which opportunities they can access outside of it. As much as we might wish it were not the case, students’ social, emotional, and mental well-being is tied up with their grades and the grading system. Online and hybrid learning has only exacerbated this and has magnified some of the fissures and inefficiencies that plague those systems. We can no longer look away.

GOA recently hosted an Ask Me Anything! Live Event: “Moving Beyond ‘Grading Everything’: Developing Sustainable Grading Practices” with a panel of teachers from its network to start talking about how we should make decisions about what and how we grade. Panelists Brande Jones (Learning Architect and Upper School Science, The Mount Vernon School), Paige Kemezis (Science Faculty, Buckingham Browne & Nichols School), Gowri Meda (Upper School Math Teacher, Oregon Episcopal School), and Tyler Rablin (High School ELA Teacher and Instructional Coach, Sunnyside School District and Shifting Schools) engaged in a cross-disciplinary conversation where they reflected on their own grading practices and articulated the shifts they’ve made to better support student learning.

You can view the full recording of the AMA below. What follows is a list of key takeaways and themes that emerged from the conversation.

GOA Ask Me Anything: Sustainable Grading Practices

Four Shifts in Grading Practice

1. From Grading Tasks to Collecting Evidence of Learning

One of the major shifts that cut across all of the panelists, regardless of discipline, was changing the way they organized their gradebooks. While some started making those changes before the pandemic, the panelists acknowledged how critical it was to stop organizing the gradebook by tasks and assignments - tests, quizzes, homework, project, etc. -and instead organize the gradebook by learning outcomes or standards.

Making this shift helped panelists move away from the mindset of “grading everything” into a mindset of “looking at a body of work” and “collecting evidence of learning.” Indeed, it became easier for both teachers and students to see the patterns and trends in learning in a way that grading individual tasks obscured. Panelists reported that students became more motivated by learning as opposed to chasing points on tasks because they started to focus on articulating how they knew they were learning as opposed to what assignment they had completed.

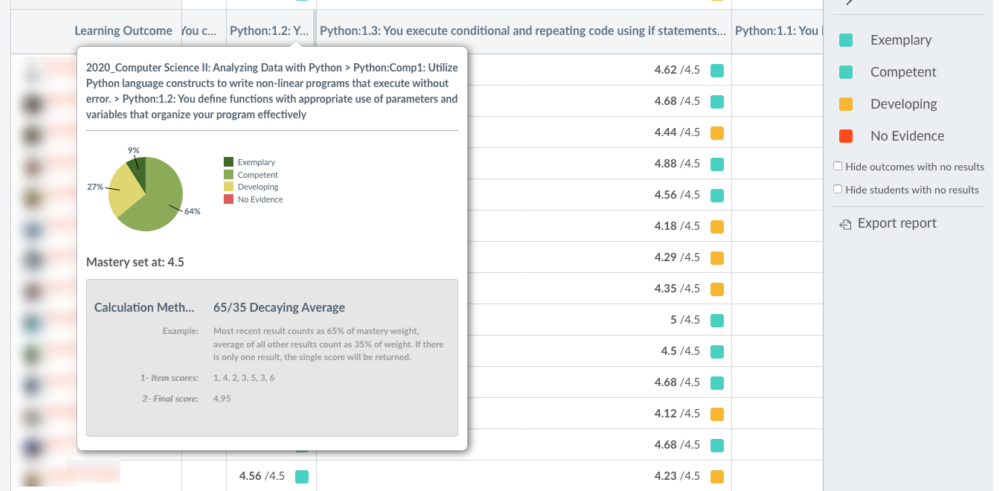

Organizing your gradebook by learning outcomes instead of by tasks, as you see here in a GOA Computer Science course that uses the Learning Mastery gradebook in Canvas, allows students to understand and visualize their performance according to specific skills.

2. From Teachers “Giving” Grades to Collaborative Grading

Coupled with the shift to collecting evidence of learning, the panelists emphasized the importance of partnering with students to determine grades. This shift to collaborative grading is a way of making the process of grading more sustainable for teachers, while also providing students with a sense of agency, ownership, and accountability. The panelists discussed asking students to identify pieces from their body of work that exemplify their learning. Then, teachers use conferences with students as a way to calibrate and arrive at a grade.

Essential to this notion of collaborative grading is leaning heavily on student self-assessment and reflection. Both Gowri and Paige mentioned that when assigning problem sets for math and physics, they often provide answer keys that students use to check their work. Where they provide feedback is on the students’ reflection of how and why they made the decisions they made, what they learned, and what their next steps are. Therefore, the focus moves away from just “getting the right answer” to having students articulate and understand how their learning can be transferable and enduring.

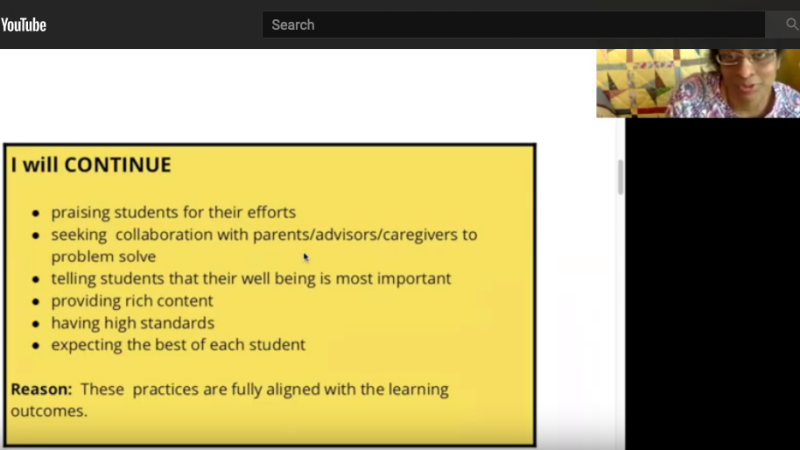

Here is a video from Gowri made during a GOA competency-based learning program that explains how her own shifts in grading will empower students.

Gowri Meda on Changing Grading Practices

3. From Grading for Reporting to Grading for Equity

A critical consideration for the panelists was making deliberate shifts in their grading practices to promote equity. Brande mentioned that a step her school made was to create a common set of rubrics across the science department that all teachers used and to norm what proficient work looked like across the rubric categories. This measure was an effort to make sure that students’ grades were not based upon who they had as a teacher, but rather on what they had actually learned.

Tyler and Paige both mentioned reevaluating the concept of averaging grades. As Joe Feldman discussed in a recent interview, “When you average a student's performance over time, you are actually perpetuating those disparities that occurred before that student came into your class.” Indeed, there seems to be something problematic about a student who shows no improvement in a class getting a higher grade than a student who demonstrated substantial growth and, thus, learned. Given that some students need more time to learn and others less, averaging performance doesn't necessarily capture growth. This is where the concept of incorporating decaying averages and reassessment may serve to promote greater equity.

4. From Labor-Intensive Grading to Tech-Enhanced Grading

The panelists also talked about how they leveraged technology and other strategies to make grading more sustainable. Tech tools like Peardeck and Poll Everywhere are ways to formatively assess by collecting real-time information about where students are in their learning. To provide feedback in an efficient and less time-intensive way, the panelists leaned on voice feedback through a tool like Kaizena, creating a Google Doc of common comments for reuse, and using text expander shortcuts.

The panelists also discussed the importance of using a consistent set of rubrics and supporting students in developing an understanding of what those rubrics mean. Tyler modifies his rubrics by adding hyperlinks to instructional resources and examples of work that explain what a particular line item on a rubric looks like. This is a way to provide students with a sense of agency and support without relying on the teacher providing feedback on every step or detail of the process.

The shifts that the AMA panelists explored fundamentally support a shift in focusing on the learning process and growth over the products of learning. What shifts have you made to your grading practice? Let us know using #GOALearning and @GOALearning.

To read more about grading and assessment, read these GOA articles:

- CBL in Action: What does it look like to revisit and reassess competencies over time?

- 15 Resources for Rethinking Assessment

- Seven Building Blocks of a Competency-Based Classroom

Are you interested in learning more about ways to rethink grading? Check out GOA’s facilitated workshops on Designing for Equity in Grading and Designing Assessments that Promote Equity, Integrity, and Rigor. We’ve also just opened up registration for two professional learning programs: Design Institute Level 1 and Design Institute Level 2.