Introducing Jam Sessions, the Learning-Focused Faculty Meeting

How often do faculty meetings focus on learning?

I once taught in a school where faculty meetings were held on Friday afternoons at the end of the class day at the end of long weeks. We’d gather in a large room, where rows of chairs faced the front, where administrators made announcements on a microphone. The timing was rough, the gatherings mostly uninspired. Rarely did the content require being in the same place at the same time. However, when an agenda item did provoke lively, if not tense, reactions, we left with little resolved and a weekend to stew.

In The Art of Gathering, How We Meet and Why It Matters, Priya Parker argues that gatherings are essential, yet many gatherings in our lives — from conferences to dinner parties and meetings at work — are unproductive if not lacking and lackluster. To eliminate mundane gatherings, Parker describes how their purpose has to be specific, unique, and disputable. Shaping such a purpose requires focusing on the why rather than the what.

Inspired by Ron Berger's work and my own experience reviewing student work with colleagues, we’re making discussing, reviewing, and analyzing student work the shared purpose of our teacher gatherings this year. We’ve renamed faculty meetings “jam sessions,” and, like a jam session, we’ll invite everyone to bring (metaphorical) instruments and aim to build something together, which wouldn’t be possible as soloists. We want faculty to leave with new ideas about assessing student work, and we want faculty to grow their competencies, especially with feedback.

To design the jam sessions, we thought broadly about communication and the topics worthy of synchronous gatherings. How might we make the most of time we spend together?

We identified three priorities in designing jam sessions:

- Make time and space for learning-focused meetings by using varied and intentional communication. Our introduction of Slack has led to efficient messaging and information sharing and has reduced a lot of email. Having a powerful communication platform frees up meetings for what’s worthy of gathering at the same time, able to see each other’s faces and body language, able to collaborate.

- Prioritize team building. In The Art of Coaching Teams, Elena Aguilar argues that teams are built, not just named or assembled. Building a team requires trust, time, skillful leadership, and emotional intelligence. Further, Aguilar believes “the health of a meeting reflects the health of a team.” We have to build the team and design meetings to focus conversations on what teachers care about most: students and their learning.

- Drive learning. We offer jam sessions as a series of smaller meetings rather than a single gathering of the entire faculty. Through a collective, more intimate look at student work, we move from what can gobble our attention — details and logistics (not that these don’t matter) — to the essential goal of this whole enterprise: learning.

What does a jam session look like?

Recently we held our first one, which began with an icebreaker to build the team and set the tone:

What’s one thing you’re learning right now? What would success in that effort look like?

The question also reflects the core belief in our approach to faculty professional learning: we believe that faculty learning increases and improves student learning.

While participants read the jam session goals and agreements before our gathering, early on we revisited them together:

- Try a collaborative process: looking for learning (outcomes) in student work and inferring what the outcomes reveal about the condition of aligned competencies

- Interpret specific outcomes to think further and learn about CBL-based assessment

- Discuss how this process aligns (or not) with current practices and what the challenges are in transitioning to this process for teachers... for students…

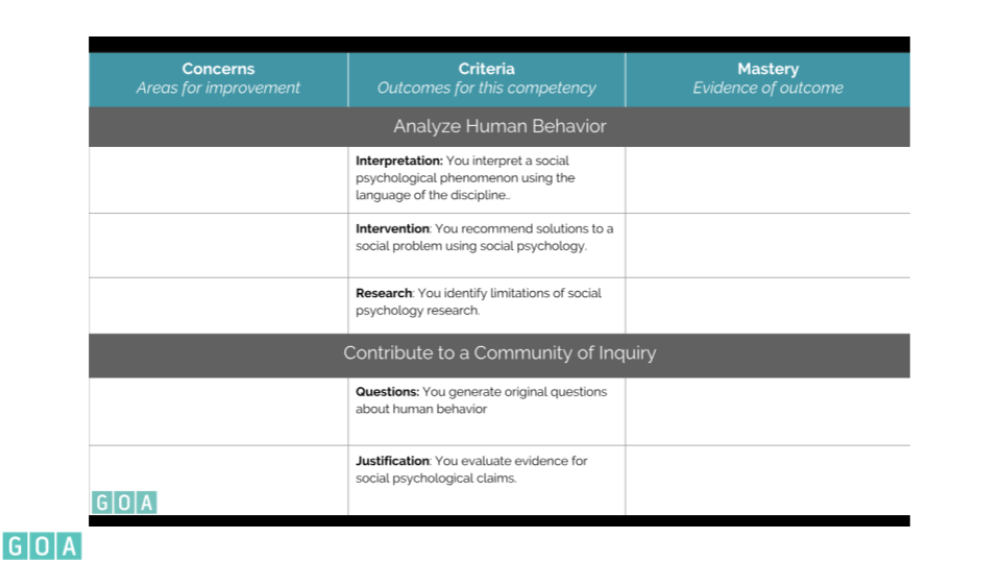

Prior to the jam session, we had reviewed an online discussion from one participant’s social psychology course, using the same single-point rubric the teacher used to assess the student work.

We discovered that it’s hard work to lean this far into student work, to talk with colleagues about what outcomes we’re seeing (or not seeing). One observation we unearthed: the students weren’t generating original questions or using the language of social psychology (two outcomes articulated on the rubric).

Because it’s early in the course, examining student work now is ideal timing for feedback that leads students to grasp what they’re being asked to do and to develop the competencies that enable doing so.

The essential act here is to make time for these conversations and reflections. Given how the largest barrier many identify for doing most everything is time, anything that saps time (or energy) from discussing learning has to go. Our inaugural jam session did focus on learning, that of students and that of the adults who support them.

How might reframing faculty meetings as jam sessions transform gatherings at your school? What ideas here would apply to your context? Let us know on Twitter or email us at hello@globalonlineacademy.org.

Take the next step in thinking differently about professional learning: sign up for one of our educator courses.