How to Create Safe Spaces for Students to Hold Courageous Conversations

Students need safe spaces to hold courageous conversations about race.

Over the past year, students have watched school leaders reckon with founding histories tied to racial exclusion. Students posted stories of experiencing racism at their schools, and streets across the world filled with protestors outraged over the continued deaths of black and brown bodies at the hands of police. Communities began to publicly acknowledge that race was at the heart of inequities, a truth magnified by the disproportionate effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Since 2019, GOA has been offering Race and Society, an interdisciplinary course in which students examine their lived experiences, their assumptions, their language, and their perspectives with respect to race. GOA teachers Joel Garza of Greenhill School and Velicia Pernell of American School of Bombay know courageous conversations require safe spaces, and I talked with them about three strategies to create authentic, safe spaces for students to hold courageous conversations. These strategies are closely tied to some of GOA's core competencies.

Three Strategies for Courageous Conversations

1. Ask Students to Start with Themselves.

In “How to Start Meaningful Conversations About Race in the Classroom,” Maria Underwood writes, “One of the most important elements of teaching race and racism is examining implicit biases that may inform your way of thinking. We all need to work on ourselves.”

The first unit of Race and Society, titled “Race, You, and Your Community,” asks students to reflect on and take responsibility for their own learning, a GOA core competency. Velicia said the first step in creating a “safe space is about students really exploring their own identities and their racial identities. For some students, especially students who never really had to think about race until recently, it’s eye opening.”

The unit’s opening activity, “Name Story,” invites students to dig into the origins, spelling, meaning, and feelings associated with their names. Joel explains how Name Story builds trust among the students which lays the groundwork for brave and vulnerable content: “By looking carefully at our names and their meanings, we confront and celebrate the cultural and ethnic and racial and religious and gendered ways that others come to know us. Sometimes my name tells you, ‘We have [x] in common’; sometimes it tells you, ‘We might have some bridge-building to do in order to understand one another.’ In clarifying who we are, in confronting what we might assume about one another, this name exercise prepares us to be brave about our biases and values, to be proud about our stories, and to be prepared to learn from one another for one another.”

Joel and Velicia model for students what it means to explore one's own identity by sharing their Name Stories with their students.

Joel Garza Name Story

My mother named me.

Joel (pronounced /hō•ÉL/) Rolando. My older brothers are Daniel Eduardo & Raul Fernando.

She chose a name that could rhyme and roll with the same syllables as my older brothers.

She chose Joel also because it is a name in the Bible, and they knew a family priest (we're Catholic) whose name was Joel. I never met him.

She did not choose my last name, Garza, which is the family name she took on when she married my father.

If I'm honest, I don't pronounce my last (or my first names) like she heard them growing up. I anglicize them: I put a kind of "w" between the syllables of my first name--not /hō•ÉL/ but /hō•WÉL/; I say GAR-zuh rather than GAR-sah.

It's an almost Mexican name, when I pronounce it. A Mexican-American name.

Velicia Pernell Name Story

My father named me.

Velicia—like Felicia—but better.

He chose Velicia after the latin word, felix which means happy.

He chose Victoria after the Queen of England.

He wanted me to be a happy princess.

He says I lived up to that name.

I was the happiest little girl

Laughing and giggling

And tumbling.

But Pernell belonged to someone else. To a legacy robbed. To a slave master.

2. Give Students Permission to Get it Wrong.

Inspired by Step Four of Alcoholics Anonymous, unit two of Race and Society course challenges students to conduct a fearless inventory of themselves, exploring the following questions posed by the course’s mentor text, Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race?:

What stories have we centered in our lives?

What are the consequences of centering those stories?

What stories have we ignored in our lives?

What are the consequences of never seeing those stories?

In an assignment titled “What if I Talk About Race Wrong?”, students start with themselves to understand intent versus impact and then learn what to do when they are responsible for unintended harm. While reminding students regularly that there is “No blame. No Shame,” Velicia explained that the permission to get it wrong while looking internally invites vulnerability, courage, and learning, a component of the GOA core competency “Communicate and empathize with people who have perspectives different from your own.”

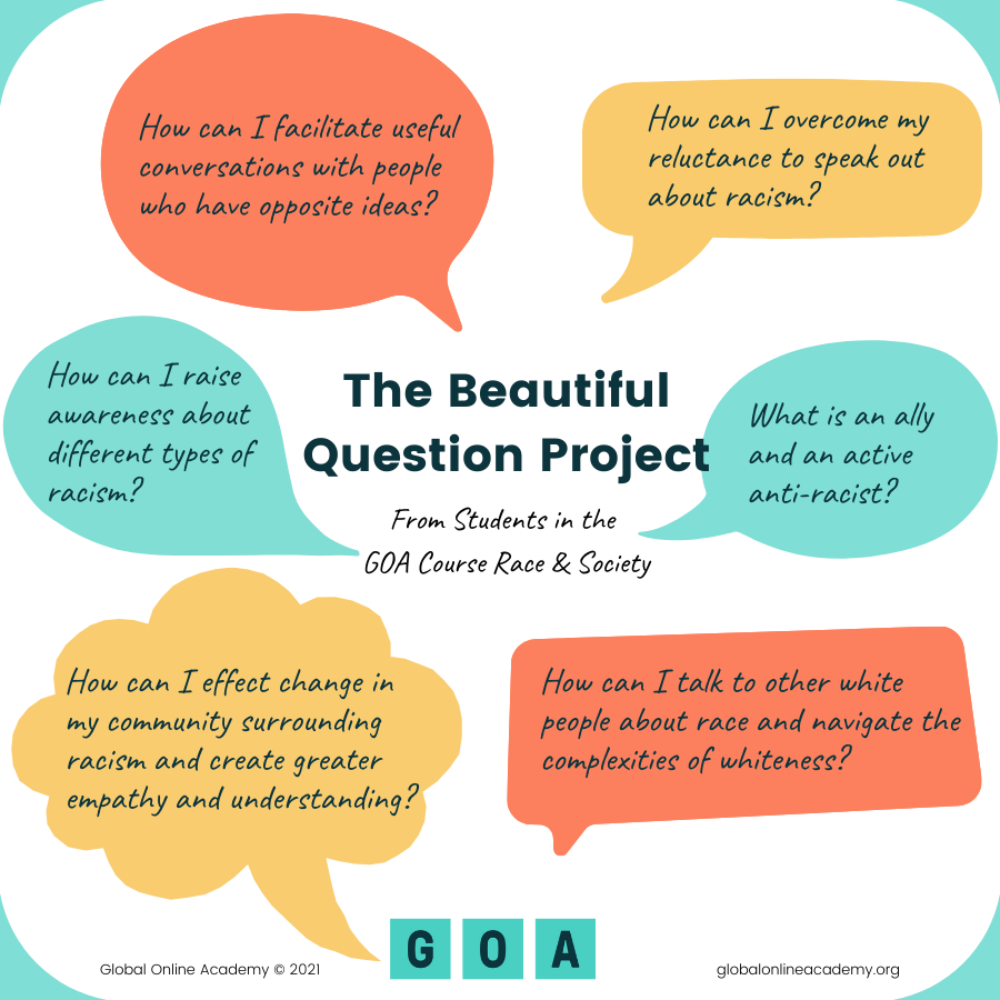

Students in Race and Society created guides for themselves and others on how to engage others in conversations about race. This is an excerpt from Yoska's (Head-Royce School) project.

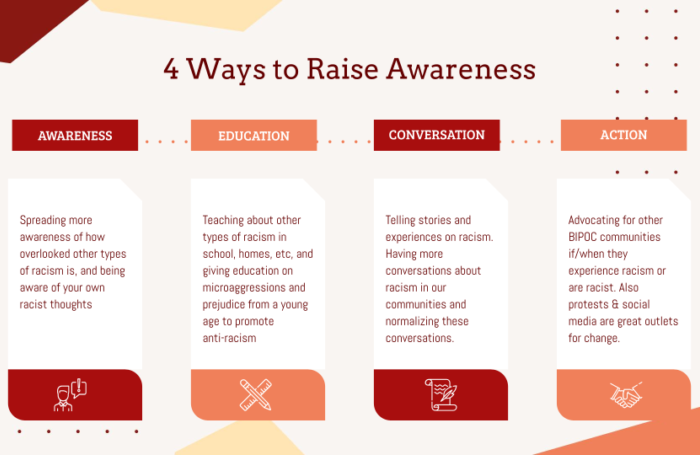

Student projects include action items for themselves and others. Excerpt of a project by Tatiana (French American International School).

Velicia added, “We’ve designed a narrative-based assignment where students are commenting on a visual representing something they have gotten wrong or some social dilemma they’ve had. Then, they’re commenting on other people’s experiences and pushing themselves to give feedback. Instead of asking questions about a community you are not a part of, ask questions about yourself. This will help you reflect on who you are and the decisions you make.”

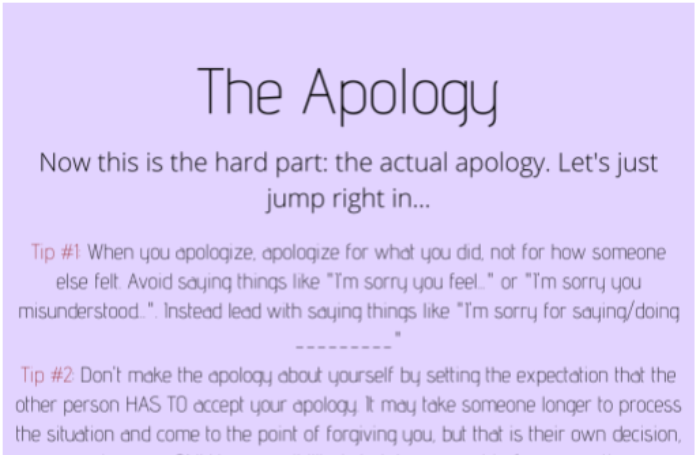

Embedded in the assignment is a guide on how to apologize after a microaggression, poor decision, or misstep around race. Students are directed to listen to the podcast Still Processing on Apology, which asks, “How can we grow into the people we want to become when we can’t acknowledge our mistakes and the effect that they've had on others?”

Sunday Morning Coffee | December 6, 2020

In addition, the teachers create the safe space in their classrooms through modeling vulnerability. Each week, Joel invites his students into a Sunday morning coffee conversation. Joel opens up about his weekend, shares what is on his mind, and then prepares his students for the week of learning ahead. In this particular coffee conversation, Joel shares a misstep he made with a friend via email the previous night. He brings it back to his students and their learning: “As you begin the work this week, keep in mind that moment that I had via email with my friend where I lined up all of the research, I had lined up my experience, I was coming from a very passionate place, AND I needed to calibrate my tone a little bit, because, we are, most of us, working on topics that are about deepening, sustaining and growing community, not winning a debate. Please learn from my mistake.”

3. Empower Students to Create a Plan.

The final unit of Race and Society empowers students to apply their learning and create a plan for change, touching on another of GOA’s core competencies: create and curate content relevant to real-world issues. By this point in the course, Velicia said, “There have been many ‘ouch’ moments, students realizing their missteps, rereading the mentor texts, feeling guilty, and having the courage to admit it. We allow them to process it by saying, ‘If you could do something differently, what would you do? Imagine yourself in the future. What do you see yourself doing now and being able to do? Envision yourself in the future.’”

“The Beautiful Question Project” invites asks students to pitch a single beautiful question and craft a response that reflects the courageous conversations and brave learning.

Joel and Velicia have curated a space where students ask courageous questions to lead to courageous explorations of race and society. When able to show up bravely, students are empowered to create a plan.

To learn more about creating safe spaces for meaningful conversations in online spaces, read these GOA articles:

- How to Cultivate Belonging in Online Learning

- Making Room for Questions, Play, Creativity, and Community: Setting a Tone for Student Driven Learning

- Four Equity Priorities for Online Learning

The GOA Student Program offers passion-based online courses to middle and high school students. Our summer courses (including Race & Society) are open to all students. GOA member schools have full access to our course catalog and mini courses. To learn more about membership, complete this inquiry form.